What Makes a Good Strategy? A 10-Point Checklist

Don’t skip from goals to tactics. Use this checklist to make sure you actually have a strategy.

Reading time: 14 minutes

You finished your strategy document. It took weeks. You presented it to leadership. They nodded along. Everyone agreed it was solid. Someone even said, "This is really strategic."

Six months later, nothing has changed. The strategy is sitting in a Google Doc that no one has opened since the presentation.

The problem isn't execution. The problem is that what you wrote wasn't actually a good strategy. It was a goal wearing a strategy costume.

This happens all the time, especially with team-level strategies like UX strategy and product strategy. We jump from "here's what we want to achieve" straight to "here's what we're going to do," skipping the hard thinking in between.

I've reviewed hundreds of UX and product strategies in my courses, and the most common mistake is this: they don't have a strategy at all. They have goals and tactics with nothing connecting them.

The strategy checklist helps you pressure-test team-level strategies with an external aspect.

Here are some examples:

UX strategy

Product strategy

Design strategy

Content strategy

Brand strategy

Customer experience (CX) strategy

If your strategy involves users, customers, or market positioning, these 10 questions apply.

I'll use UX strategy examples throughout, but the principles work for any customer-facing strategy.

This checklist will help you catch that mistake before you waste months on a strategy that isn't one.

Ready to have your strategy torn to shreds? Just kidding, I’ll be gentle.

The Problem: Goals Disguised as Strategy

In my article What is Strategy, Really? I break down strategy into three layers: Goals, Strategy, and Tactics.

Goals are the outcomes you want to achieve (the why). Strategy is the approach you’ll take to reach those goals (the how). Tactics are the specific actions and deliverables (the what).

Most people skip the middle layer entirely. They write down a goal like “increase user retention by 20%” and then jump straight to tactics like “redesign the onboarding flow” and “add a loyalty program.”

That’s not a strategy. That’s a to-do list with ambition.

A real strategy explains why those tactics will work. It identifies the core challenge standing between you and your goal, and it articulates a clever approach to overcome it.

Richard Rumelt, one of the world’s leading strategy thinkers, calls this the “diagnosis.” Without it, you’re just guessing.

Try it now: Look at your last strategy document. Can you point to the part that explains why your approach will work? If it just lists what you want and what you’ll do, you skipped the strategy.

What Makes a Real Strategy

"Good strategy is rare. Bad strategy is everywhere."

That’s Richard Rumelt, author of Good Strategy Bad Strategy and possibly the only strategy thinker whose book title doubles as a brutally honest performance review.

Rumelt argues that a real strategy has three components (he calls this the “kernel”):

Diagnosis of the challenge. What’s the core problem or opportunity standing between you and your goal? Not a list of everything hard. One focused root cause.

Guiding policy. The approach you’ll take to overcome the challenge. Not a tactic. A principle that is high-level enough to guide decisions for years.

Coherent actions. Tactics and activities that implement your guiding policy (and build upon each other in a combination of moves).

Most “strategies” are missing #1 and #2. They jump straight to #3, which means their tactics are just a to-do list with no basis in reality.

This checklist tests whether your strategy has all three components, and whether they’re actually good.

The Strategy Checklist: 10 Questions

The strategy checklist works for any team-level strategy: UX strategy, product strategy, design strategy, content strategy, etc. It’s not designed for company-wide business strategy (that’s a different beast), but for the strategies that guide how your team approaches its work.

Fair warning: this checklist might hurt. If you’ve been calling something a “strategy” for months and it fails question #1, that’s going to sting. But better to find out now than six months into execution.

For each question, I’ll explain what it’s testing and give you a UX strategy example.

Is this strategy more than a goal?

Does your strategy provide the “how,” not just the “what you want”?

A goal tells you where you want to end up. A strategy tells you how you’ll get there. If your strategy document could be summarized as “we want to be better at X,” you don’t have a strategy.

Bad example: “Our UX strategy is to become the most user-friendly product in our category.”

That’s a goal. It tells you nothing about how you’ll achieve it.

Good example: “Our UX strategy is to reduce complexity by focusing on the three tasks that account for 80% of user activity, and hiding everything else behind progressive disclosure.”

That’s a strategy. It identifies an approach (reduce complexity through focus) and a mechanism (progressive disclosure).

Ask yourself: If someone asked “but how will you do that?” after reading your strategy, you probably just have a goal.

Did you do your research with this strategy?

Is your strategy grounded in evidence, or did you brainstorm it in a workshop?

Strategy should look more like a research project than a brainstorming session. You need data about your users, your market, and your organization’s capabilities. Without research, you’re just making educated guesses.

Bad example: A UX strategy based on a two-hour workshop where the team wrote assumptions on sticky notes and voted on them.

Good example: A UX strategy informed by user interviews, analytics data, competitive analysis, and stakeholder conversations, where the team synthesized patterns before deciding on an approach.

Research doesn’t mean perfection. You don’t need six months of studies. But you need more than opinions.

Ask yourself: What evidence would change your strategy? If you can’t answer that, you probably didn’t gather enough evidence to begin with.

Does your strategy address an important challenge?

Is your strategy focused on overcoming a real obstacle/grasping a specific opportunity, or is it just a list of aspirations?

Good strategy is about overcoming challenges. If your strategy doesn’t name a specific challenge you’re trying to solve, it’s probably just a list of things you hope will happen.

Bad example: “Our UX strategy focuses on delight, accessibility, and consistency.”

Those are nice themes, but what challenge do they address? This reads like a list of values, not a strategy.

Good example: “Our users abandon complex tasks because our interface requires too much cognitive load. Our UX strategy focuses on reducing decision points and providing clearer guidance at each step.”

This names a specific challenge (cognitive overload causing abandonment) and positions the strategy as a response to it.

Ask yourself: What problem does your strategy solve? If you can’t name it in one sentence, your strategy might be too unfocused.

Would it make sense to do the opposite of this strategy?

Is your strategy making a real choice, or is it just stating the obvious?

A good strategy involves trade-offs. If no reasonable person would choose the opposite of your strategy, you haven’t made a real choice. This is called the strategy sniff test, and it’s a great way to see if you have a strategy or not.

Bad example: “Our UX strategy is to create products that users love.”

Who would choose the opposite? “Our strategy is to create products users hate.” No one is putting that on a slide. This isn’t a strategy. It’s a platitude.

Good example: “Our UX strategy prioritizes power users over new users. We’ll optimize for efficiency and depth, accepting that this creates a steeper learning curve.”

The opposite (prioritizing new users over power users) is a legitimate choice that many companies make. This strategy has teeth.

Ask yourself: State the opposite of your strategy out loud. If it sounds absurd, your strategy is too generic.

Is it doable to implement this strategy?

Do you have the resources, skills, and organizational support to actually execute this strategy?

A brilliant strategy you can’t execute is useless. Check whether your team actually has the capabilities to pull this off.

Bad example: A UX strategy that requires machine learning personalization when your team has no ML expertise and no budget to hire for it.

Good example: A UX strategy that leverages your team’s existing strength in user research to create a continuous feedback loop that competitors (who don’t invest in research) can’t match.

Strategies that build on existing strengths are more likely to succeed than strategies that require you to build entirely new capabilities.

Ask yourself: What would need to change in your organization for this strategy to work? If the list is long, your strategy might be too ambitious for your current reality.

Will this strategy help differentiate us from competitors?

Does your strategy create meaningful separation from alternatives, or will you blend into the crowd?

Strategy is about positioning. If your strategy leads you to the same place as everyone else, it’s not much of a strategy.

The biggest trap here? Best practices. Following best practices is important for baseline quality, but it’s the opposite of differentiation. If everyone follows the same best practices, everyone ends up in the same place. Best practices are table stakes, not strategy.

Bad example: “Our UX strategy is to follow industry best practices and ensure our product meets user expectations.”

Congratulations, you’ve just described every competitor. This is a recipe for being average.

Good example: “Our UX strategy is to be radically transparent about our product’s limitations, helping users understand exactly what they’re getting. Competitors hide their flaws; we’ll build trust by exposing ours.”

This is a choice that creates differentiation. Not every company would (or should) make this choice, which is exactly why it’s strategic.

Ask yourself: If a competitor read your strategy, would they think “we should do that too”? If so, it’s not differentiated enough.

Will the strategy’s advantage be defendable?

Can competitors easily copy your strategy, or does it create a lasting advantage?

Some strategies are easy to copy. If your advantage comes from something competitors can replicate in a few months, it’s not much of a moat. It’s a speed bump.

Bad example: “Our UX strategy is to add dark mode and better icons.”

Any competitor can do this by next quarter. It’s a feature, not a strategy.

Good example: “Our UX strategy leverages the deep domain expertise we’ve built from 10 years working exclusively with healthcare compliance teams. We understand their workflows in ways that generalist competitors can’t match without years of specialization.”

This advantage is based on something competitors can’t easily copy: accumulated expertise and customer relationships.

Ask yourself: How long would it take a well-funded competitor to copy your strategy? If the answer is “a few months,” keep thinking.

Is this strategy aligned with our customers?

Does your strategy align with what your customers actually value, need, and do?

Customers make or break a strategy. You can have the cleverest approach in the world, but if customers don’t care, it won’t work.

Bad example: A UX strategy focused on gamification and social features for an audience of time-pressed professionals who just want to get their work done quickly.

Good example: A UX strategy focused on speed and efficiency for that same audience, removing every unnecessary step and interaction.

This seems obvious, but it’s easy to get excited about an approach that doesn’t match what your users actually want.

Ask yourself: Have you validated your strategy direction with real users? Not just the problem, but the approach?

Is it aligned with strategies above it in the org chart?

Does your team-level strategy support the higher-level strategies of your organization?

A UX strategy should align with your product strategy. A product strategy should align with your business strategy. If these layers are pulling in different directions, someone is going to lose.

Bad example: A UX strategy focused on delighting consumer users when the company’s business strategy is shifting toward enterprise sales.

Good example: A UX strategy that explicitly supports the product strategy’s focus on expanding revenue by improving the upgrade experience and making premium features more discoverable.

Before finalizing your strategy, make sure you understand what’s happening at the layer above you.

Ask yourself: Can you articulate how your strategy supports your organization’s broader goals? If not, don’t be surprised when leadership suddenly has “concerns” about your direction.

Will there be a desire to execute this strategy?

Did you involve others in the strategy design process? Are you telling the right story about your strategy? Will people want to implement it?

Strategy requires buy-in. If the people who need to execute your strategy don’t understand it, don’t believe in it, or don’t want to do it, execution will be a struggle.

Bad example: A technically brilliant UX strategy that was developed in isolation and handed down to a team that wasn’t consulted. There won’t be much excitement.

Good example: A UX strategy that was developed collaboratively tells a compelling story about why this approach will work and gives the execution team ownership over the details.

The best strategy in the world fails if no one wants to execute it. Storytelling and involvement matter. A strategy that people believe in will outperform a “better” strategy that people resent.

Ask yourself: Have the people who will execute this strategy helped shape it? If not, good luck.

How to Use the Checklist

The strategy checklist isn’t a pass/fail test. It’s a diagnostic tool.

Aim to check at least five boxes. If you can honestly say “yes” to five or more questions, your strategy is probably solid enough to move forward with.

Use the unchecked boxes as improvement areas. Each “no” tells you where your strategy might be weak. Maybe you need more research. Maybe you need to sharpen your focus. Maybe you need better alignment with leadership.

Review the checklist at key moments: before you finalize a strategy, when presenting to stakeholders, and when a strategy isn’t working.

The checklist works best as a conversation starter with your team. Go through each question together and discuss where you’re strong and where you’re vulnerable.

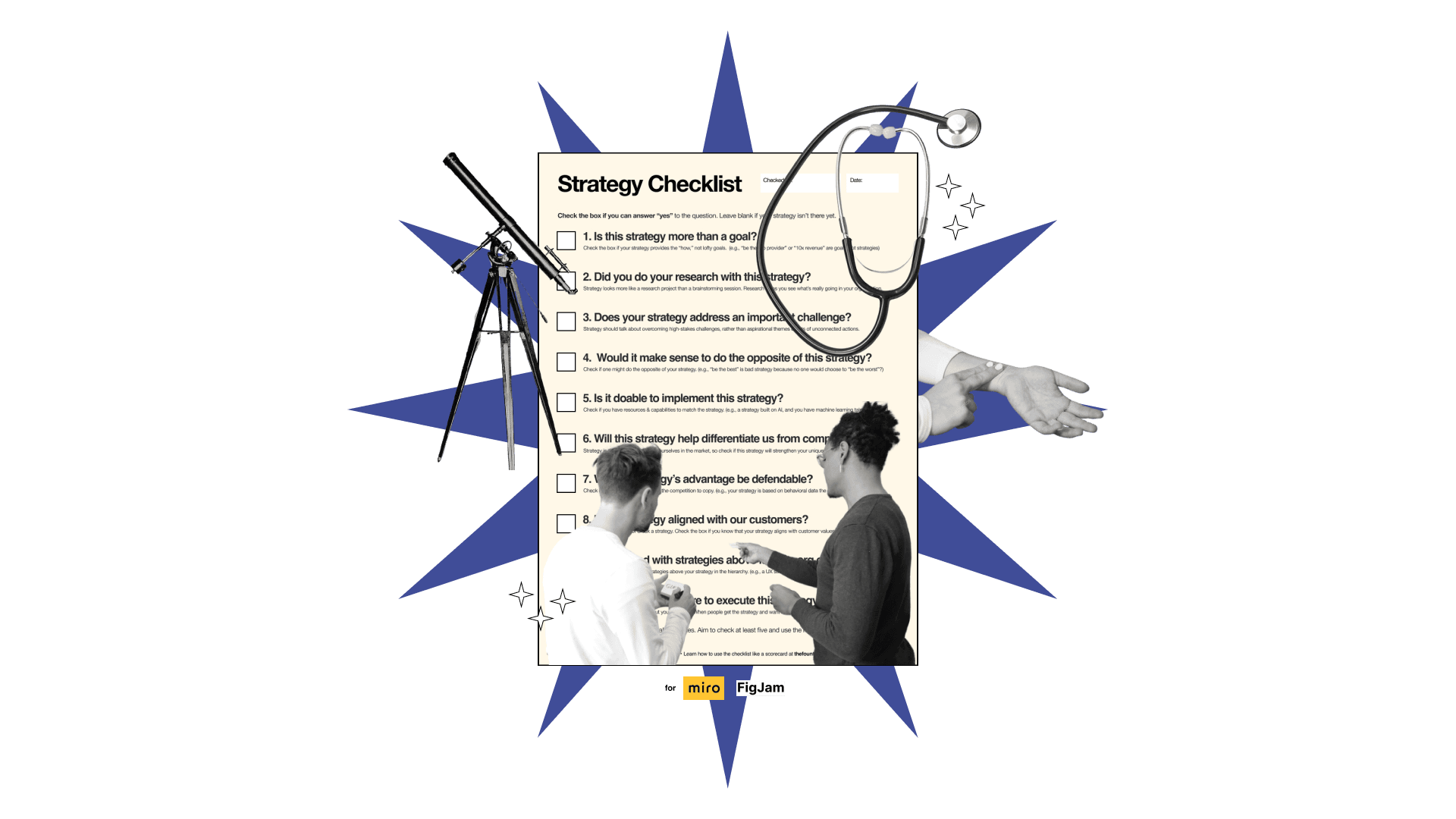

Download the Free Checklist

Ready to test your strategy? Download the PDF below.

Print it out or drop it in Miro. Bring it to your next strategy review.

Use it to pressure-test your thinking before you commit to months of execution.

Want to design better strategies?

The checklist helps you evaluate a strategy. But how do you design a good one in the first place?

I teach a course called Defining UX Strategy, where you’ll learn:

How to research and diagnose strategic challenges

How to facilitate strategy workshops with your team

How to test and adapt your strategy

How to write strategies that pass this checklist

The course includes live workshops, detailed video lessons, and hands-on practice with strategic frameworks. You’ll leave with a complete UX strategy you can implement immediately.

Learning Resources

What is UX Strategy, Really? - The Goals, Strategy, Tactics framework explained

The UX Strategy Template Your Team Actually Needs - A one-page canvas for designing strategy

UX Strategy vs Product Strategy - How these two disciplines relate