The Designer’s Guide to Testing and Experiments

A guide for designers that want to test design ideas for innovation

Reading Time: 25 minutes

In 2020, Google conducted over 600,000 experiments [source]. Netflix experiments so much that they designed a custom testing platform so that the Netflix you see is different than the Netflix that your neighbor sees.

Rapid experiments allow companies to test their way to entirely new approaches. Experiment-driven decisions are quickly becoming the default way top tech companies make decisions.

“72% of all new products flop.”

Why should you be doing rapid experimentation as a designer? 72% of new products and services fail. (Kucher 2014) For startups, that number can go as high as 90%. (Startup Genome 2011)

Yikes! Is designing a good product really that risky? Once you realize that products fail more than they succeed, you should see why upfront testing and experimentation are so important.

Rapid Experimentation is the smallest, quickest, dirtiest experiment you can run. Rapid Experiments test your riskiest assumptions through customer behavior. Experimentation helps you design human-centered products because customers decide what gets built through their behavior. Rapid experimentation isn’t just a way to release.

Who wants to spend their life designing products people don’t want or need? Rapid Experimentation helps us avoid waste in our product design process. Through rapid, iterative learning, you can design better products.

The rise of rapid experimentation is a great thing for design because, at its core, rapid experimentation is about letting the customer decide what should and shouldn’t be built through their behavior. What could be more human-centered than that?

We think an Experimental Mindset is key to harnessing the power of experimentation. Sadly, this mindset isn’t taught in design schools yet. So I’ve devised a few principles you can use to train that mindset.

How to Design Experiments

Designers can easily work in a system of experimentation, but design schools don’t teach an Experimental Mindset needed on data-driven teams at Amazon, Netflix, and Google. An experimental mindset is about proving yourself wrong as quickly as possible, a classic tenet of the scientific method. What does that look like in design?

Here are seven principles that will help you build an Experimental Mindset. These are the instincts you will need to train to work on teams doing rapid experimentation.

Test assumptions. Don’t test ideas.

Every prototype should be a test.

Test Desirability, not just Usability.

Convince with data, not opinions.

Design quick and dirty, not pixel-perfect.

Design experiments bold enough to “fail.”

Generate evidence critically.

1. Don’t test ideas. Test assumptions.

Hidden beneath every idea are giant assumptions about how something will go. Humans are terrible at predicting the future so we fill in the gaps with assumptions.

Assumptions are little beliefs that we accept as accurate without proof. They’re the little leaps of faith we take when we guess our ideas will work.

An assumption is something we take for granted. Maybe it’s an accepted rule of thumb or something we learned about our users a long time ago and do not question.

Assumptions are the biggest enemy of your design ideas. Design ideas that make sense on paper can fail if they don't understand the realities of messy humans in a chaotic world.

Example:

Two designers are working on a new product, and they’re stuck. The product is based on Open A.I.’s Chat GPT. The problem is, they’re not really sure what the new product should look like. Both come to different conclusions based on their assumptions…

Designer 1’s Assumption: When people realize this paid product is powered by Chat GPT, they won’t want to pay.

Result: Designs a visual interface with no text-based inputsDesigner 2’s Assumption: Users already know how to use Chat GPT so they will expect the same design pattern for similar products

Result: Design a text-based interactions for the new product

There isn’t much evidence so both designers think their design decisions make the most sense. However, after looking at each other’s assumptions, they see the merits of both design approaches. They decide to test their assumptions with a quick lo-fi experiment.

As you can see, assumptions can affect our decisions. When everyone on the team makes assumptions, the situation can become disastrous.

In design school, we are taught to follow the brief without question, but briefs are full of assumptions. Questioning the assumptions within ideas can sometimes feel like a “buzzkill” when the team is on a creative high, but it’s an excellent way to bring reality into projects. Not sure if you have an assumption?

Every idea is an assumption until it’s in the hands of a customer.

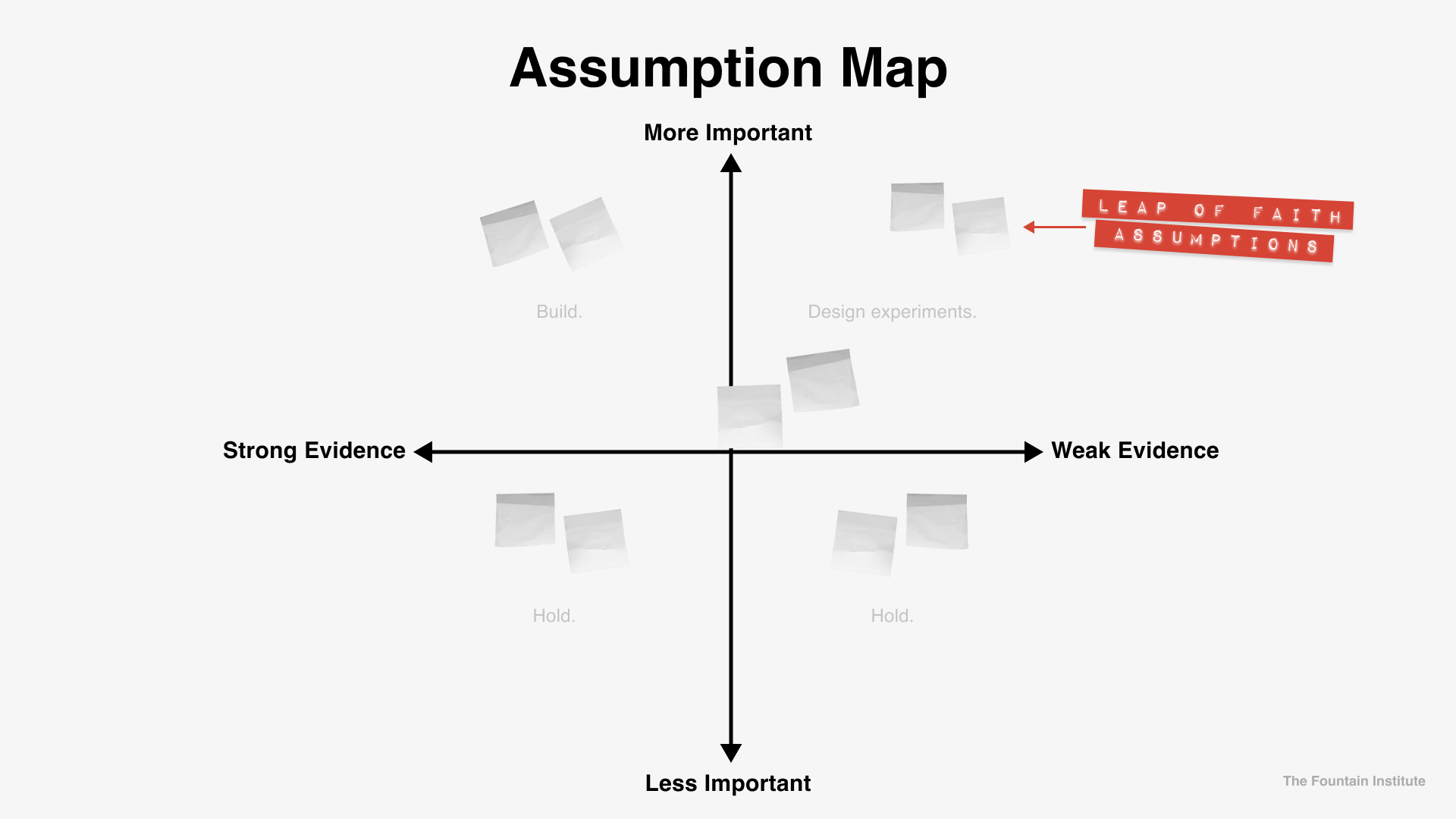

Because assumptions are beliefs, they’re not always easy to identify. Assumption hunting is finding hidden beliefs within product ideas, and it’s best done with other people. Methods like assumption mapping, user story mapping, and even a Lean Canvas can help you identify the risks with your team.

[Aim your experiments at the top-right quadrant for the best experiments]

Once you have those assumptions out in the open, it's usually quite clear that risky assumptions need to be tested.

When you're working in highly uncertain environments like on innovation teams, opinions mean nothing. Only the evidence behind the ideas matters, and that evidence should come from the customer or research, not the HiPPO (highest paid person’s opinion).

Assumptions are everywhere, but that doesn't mean finding them will be easy.

Sometimes, you have to simulate the idea to reveal the assumption. Paper prototypes, storyboarding, and journey mapping can also help you recognize gaps and areas where your team is making assumptions.

Example:

Your team had a brainstorm where you came up with an idea for a new feature. Instead of putting the idea into the roadmap, you decide to test the assumptions in the ideas first. You decide to facilitate an assumption mapping session with your team. The team comes up with some shocking assumptions that would sink the idea if they’re not true. You notice an assumption in the top-right corner. It says: “Users want to share their data in a downloadable PDF.” Since downloading the PDF is a key functionality for the idea, your team decides to test that assumption before you work on the full solution. You design an experiment with the Experiment Card and start generating some evidence for this assumption. You realize that users prefer a CSV file, and it changes everything. The idea doesn’t really make sense as a CSV so you decide to move on to the next idea.

2. Every prototype should be an experiment.

With the popularity of UX, the word prototype has lost its original meaning. By definition, a prototype is a test.

A prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process...Prototyping serves to provide specifications for a real, working system rather than a theoretical one.

In other words, prototypes are simulations for learning about the practicality of your idea. Prototypes should be tests where you learn something about customer behavior.

While prototypes can be helpful communication tools for stakeholders, that is not their purpose. There’s a popular phrase about prototyping that the marketing machine of IDEO has turned into a mantra:

"If a picture is worth 1000 words, a prototype is worth 1000 meetings."

-IDEO

A prototype can certainly reduce meetings by communicating the idea to stakeholders (crucial in the agency world when stakeholders are your clients), but the true purpose of prototypes is to learn about your concept from people that might use it.

Prototypes should demonstrate the functionality of your product idea in such a way as to simulate an early reaction from a customer. The resulting customer reactions can be qualitative or quantitative in nature. When product ideas are in their infancy, qualitative customer behavior is a great early indicator of the idea’s potential.

Example:

We made a prototype to test some of the basic functionalities of our new product. We simulated the real-world environment with a prototype in Figma shared on Zoom so we could get authentic emotional reactions from the customer. 7 out of 10 customers reacted favorably. 9 out of 10 were able to use the experience without instruction from the facilitator.

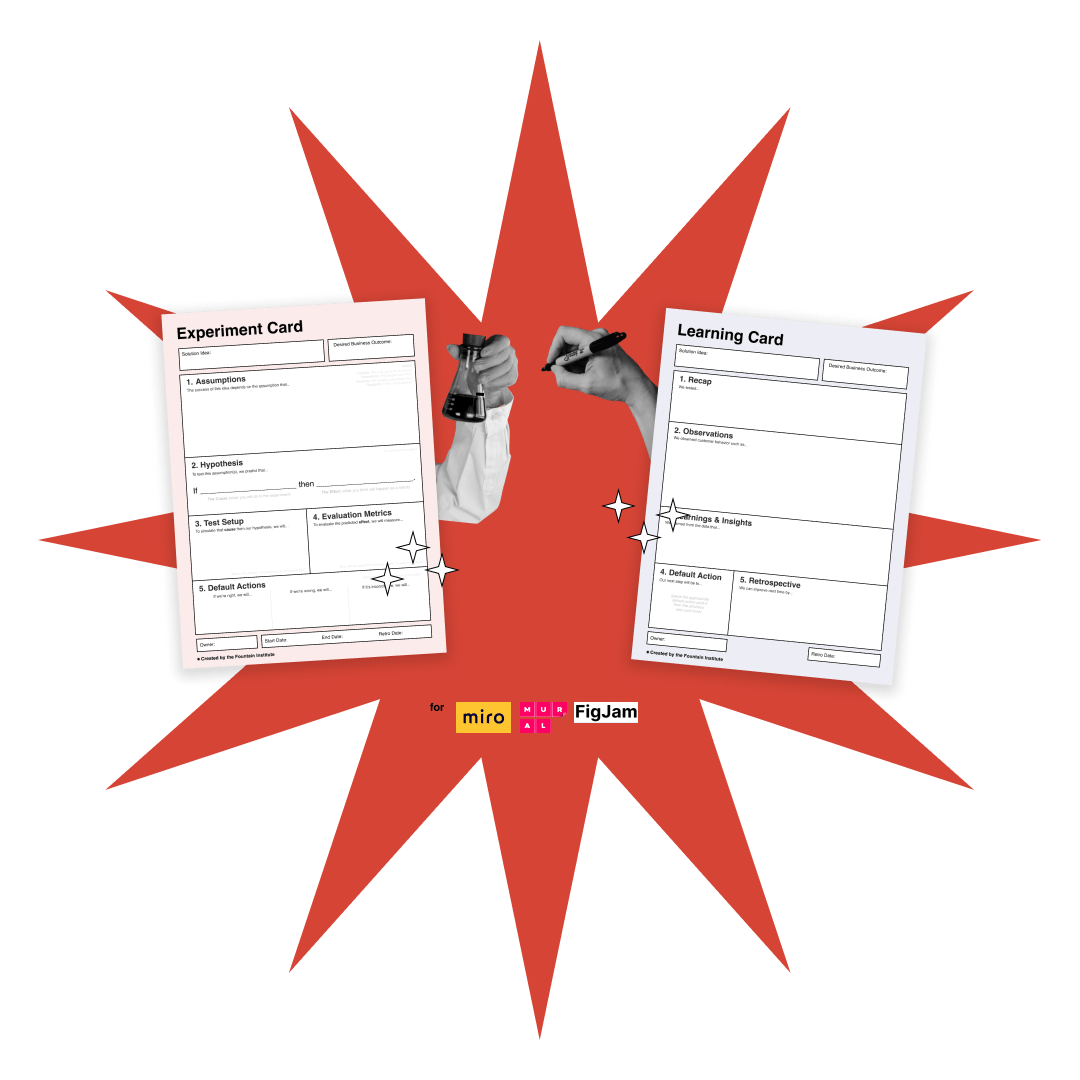

Turn Prototypes into Experiments

Use the Experiment Cards to set up your experiments like a scientist and hunt down the assumptions within your design ideas.

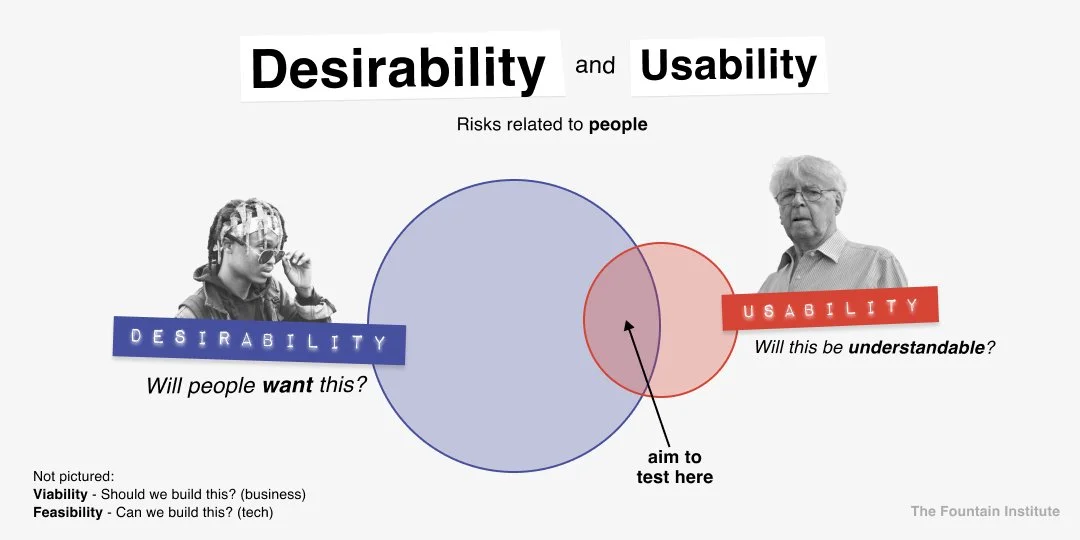

3. Test Desirability, not just Usability.

Since the 90s, interaction and UX designers have become known for handling the usability of products. But the usability of a product is useless if nobody wants it.

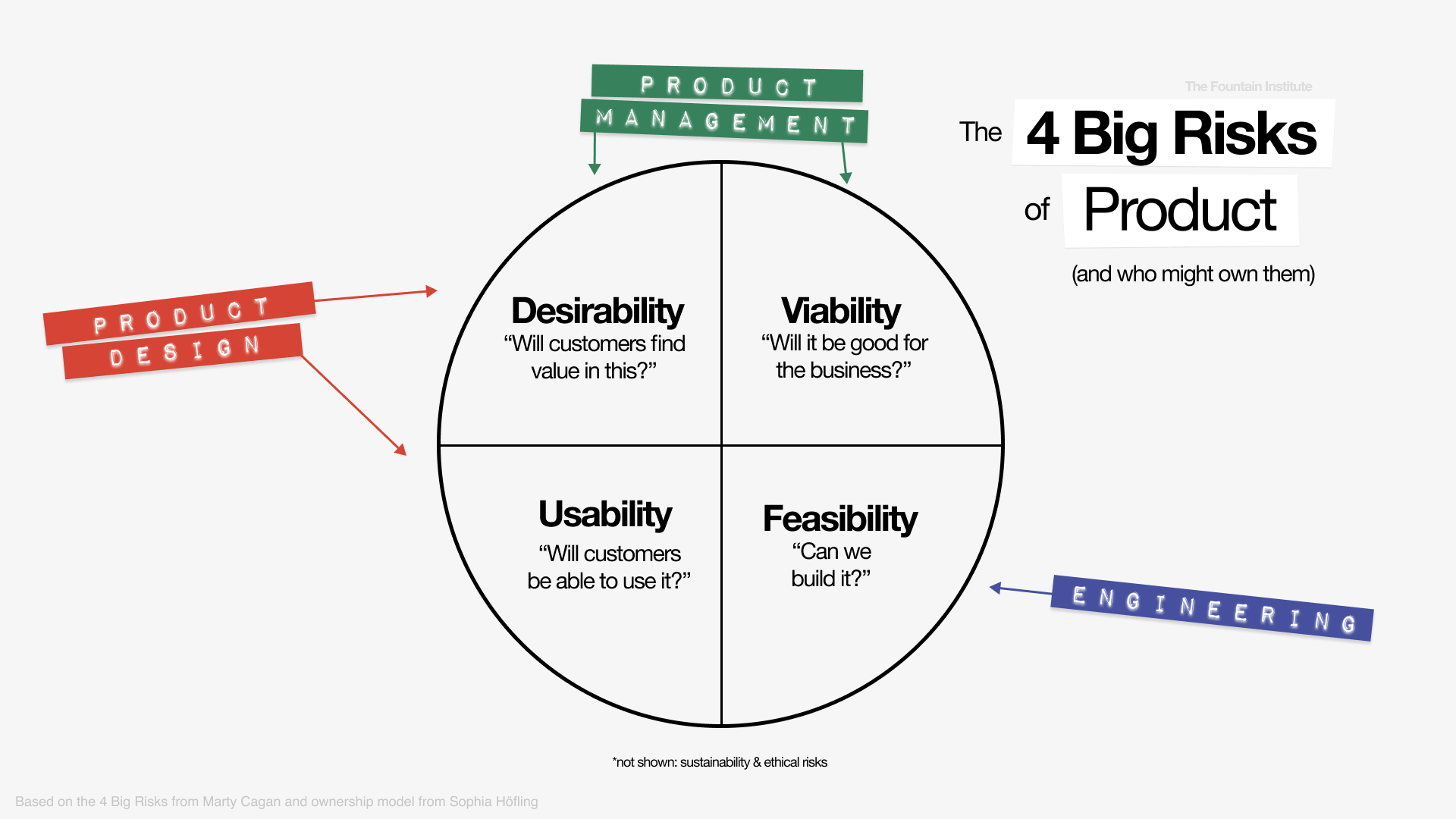

How do you ensure that you don’t have perfectly designed products that nobody wants? By mastering the 4 big risks of product.

The 4 Big Risks of Product

The four big risks of products are viability, desirability, feasibility, and usability (some teams also include ethical and sustainability risks). Let’s break down the 4 risks to good product design.

Desirability, a.k.a. Will customers find “value” in this?

Desirability, also called “value,” is customer-determined because only customers can decide if something is desirable. When we make assumptions about desirability, we guess what people will like, want, or need. Guessing is exactly the kind of decision-making that experiments help you to avoid.

Designers should seek to test desirability as soon as possible because customer adoption can be the biggest killer of design ideas. Product managers also deal with desirability so collaborate with them early in the project. Don’t assume you will have the agency to test desirability at your company.

To get at the desirability, ask questions like this:

“What evidence do we have that customers are interested in this feature?”

“Do we have some proof that this idea has momentum with customers?”

“How can we de-risk the adoption of this idea?”

Usability, a.k.a. Will customers be able to use this?

Usability is often tested through observation and behavioral data. You’re looking for the optimum design that is intuitive for your users. When we make assumptions about usability, we guess how people will use and interact with our solutions…a risky game when we forget that our users aren’t us. UX and Product Designers should be experts at identifying risks in usability.

Usability Testing is UX Design 101, but many designers don’t learn how to test desirability until later in their careers. A common path to Desirability Testing is through early-stage innovation work at startups. Many designers that master this type of work call themselves Business Designers or take on product management roles.

Viability, a.k.a. Will this be good for the business?

Viability is generally the call of product management. Any risk related to the business, revenue, and long-term goals will fall under viability. Ideas can excite customers, work well, and be easily built, but it's a viability risk if they don’t improve the business.

Designers should understand the business well enough to know when the viability risk is too great.

Feasibility, a.k.a. Can we build this?

Feasibility is generally the engineers' call, and it usually happens once you’ve de-risked the other aspects of the product. But it’s good to check this risk with your developers sooner rather than later. If you wait until the project is ready to build, you may discover that what you’ve planned isn’t possible.

Designers should have a general idea of what is possible for the engineering team to avoid unnecessary feasibility risks in their solutions.

Example:

You’re working on a new AR device that attaches to reading glasses. You have the experience mostly finished, but you decide to run a test to see if customers will find the new interactions to be intuitive. You give a few working versions to a Beta testing group. The product is usable, but surprisingly, the people interacting with your Beta testing group don’t appreciate the fact that there is a camera pointed at them at all times. Your team realizes that the product isn’t desirable to the people interacting with the new AR device, and you have to scrap the entire project. Next time, you will make to test the desirability before you get too far in the usability of the Google Glass—I mean product.

Pro Tip: Try to test both Usability and Desirability and try to test Desirability first. You want some evidence of the Desirability of an idea before you get too far into the Usability testing of an idea. In other words, test the “why” before the “how.”

4. Convince with data, not visuals.

In design school, you’re taught to communicate your ideas using visuals. When you want to convince a stakeholder of the merits of your ideas, you show them what it might look like. Visualizing ideas is an extremely valuable skill that shouldn’t be used to convince customer-focused teams. If you try to use visuals to convince a data-driven team of something with data, you’re simply decorating your opinions.

In data-driven innovation teams, opinions mean nothing unless backed by evidence. The highly uncertain environments of early-stage product work mean nobody has “expertise” in the area, and you rely on experiments to learn.

Remember, when we’re testing desirability, only customers can determine the value of an idea, so your evidence should be customer data...and ideally behavioral data. It's difficult to gauge whether something will be a good idea without looking at customer behavior.

Instead of convincing stakeholders with visuals, show visuals to customers and share the resulting behavioral data with stakeholders. That data can qualitative as well as quantitative. Here are some ways to do that:

Conduct a Preference Test

Run a 5-Second test

Make an early prototype and test it with users (see #2 below)

It’s an extra step, but it will provide some early data to de-risk the decisions your team has to take.

Example:

You wireframed two different approaches for a landing page, but you’re not sure which one is the right one. You set up a quick preference test with a tool like UserTesting and get instant results to provide a little evidence for your approach before tomorrow’s meeting. You present your early evidence to the stakeholders, and the conversation is very productive.

Pro Tip: Study customer behavior, not opinion. Avoid asking customers what they would like. Humans are very bad at predicting their future desires. Instead, ask about recent behavior or observe them completing a task.

5. Design quick and dirty, not pixel-perfect.

When you start working in rapid experimentation, you will be slow at designing experiments. But eventually, you want to pick up the pace. This is rapid experimentation, remember?

In design school, we’re taught to design things with a careful eye for detail, but that will slow you down when you’re experimenting. To design experiments with the right mindset, ask yourself, “What is the fastest, easiest, and cheapest way to test this idea?” You don’t always have to design a fancy clickable prototype in Figma.

Here are two ways to hack something together for an experiment that might be faster than a high-fidelity click test:

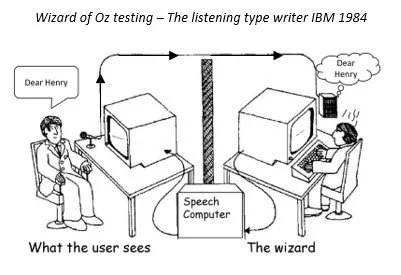

Concierge Test - Approximate functionality manually to study usage behavior and reactions in a Beta-testing group (hack is known to the user)

Wizard of Oz Experiment - Fake the functionality manually to study usage behavior and reactions in a simulation (hack is unknown to the user)

A quick and dirty discovery experiment is an emerging concept known as the Minimum Viable Experiment (M.V.E.), and it’s meant to provide learning to the team. The Minimum Viable Product (M.V.P.) comes later, and it’s meant to provide value to the customer in a release of limited functionality. [source]

M.V.E.s won’t require the level of polish that the M.V.P. requires. Learn quickly and move on to the next assumption as you methodically de-risk your solution ideas.

Remember, experiments are supposed to be quick. If they’re scrappy and you’re tooled up properly, you can design ten experiments in the time it takes you to design one pixel-perfect solution. Scrappy experiments will create shorter learning loops so don’t get caught up in tiny details when designing experiments.

Example:

You’re designing a prototype to test the desirability of a new chatbot functionality in your app. You wonder if you should do it in Figma or as a paper prototype. You ask yourself what’s the fastest, easiest, and cheapest way to test the messaging. Aha! You realize that you can test all of the functionality using existing messaging platforms. You decide to do a Wizard of Oz test where you pretend to be a chatbot using iMessage on your computer. When the user arrives, they have no idea that a human is behind the messages they’re receiving. You learn some so many useful things, and you didn’t have to design or build anything!

Pro Tip: Before you design anything custom, ask yourself, “Does this technology I’m testing already exist?” Often some tools approximate the functionality you wish to test. To do this, find existing tools with ProductHunt and link them using Zapier.

6. Design experiments bold enough to “fail.”

Most experiments will “fail" but it’s not a failure if you’re learning. If you design safe experiments that always succeed, you aren’t going bold enough and won’t learn anything.

Product experiments are like bets. The riskier the bet, the higher the payoff. The more bets you place, the more chances you will get to win. Since we know that we live in a messy world that is hard to predict, we try to design bold tests and let the learnings surprise us.

In school, we learn that design is about making detailed plans, but these plans almost never stand up to reality. We have to let go of the idea that we can predict the future. Rapid experimentation utilizes the power of chance, not carefully designed plans.

Because innovation is most often the result of chance, it’s best to design experiments that capitalize on that fact. If you let fear of failure keep you from designing bold bets, your team might give up on experimentation before they see the benefits.

Example:

Your company is trying to do more testing, and the marketing team wants to start testing some of the visual brand assets. They ask if you could help them A/B test the button color. You say that you’re happy to help and suggest that they test a big, risky assumption within that idea. You set up a 5-Second Test with 4 bold, new directions for the brand. You run that test with hundreds of users on UsabilityHub and the marketing team has a ton of qualitative insights. You use those insights to come up with an experiment that will generate more important learning on the brand.

Experiments take time to show returns. Be upfront with your team about the time it will take for experiments to pay off.

[Inspired by Nassim Taleb’s article on innovation and chance]

Pro Tip: If you’re just starting to run experiments with your team, you should let everyone know that the first few experiments are more about learning experimentation itself. If your team expects huge payoffs immediately, they won’t have patience through the “failures” of tests that don’t have huge payoffs.

7. Generate evidence critically.

When you design experiments that are meant to prove your own ideas, you will run into a little thing called Confirmation Bias. Confirmation Bias will blind you to the true nature of your experiment results, and it is the biggest barrier to proper experiment design. Instead of looking for data to prove your idea, set up a bold experiment that will give decision-makers the evidence to make better decisions.

When ideas are in their infancy, even a little bit of qualitative evidence can tell you if customers find value in your idea. Once your idea has some evidence to back it up, you can move forward with the next experiment.

Your priority as a UX or Product Designer should be to generate evidence for decision-makers. If you’re a business designer or team lead, your priority should be making evidence-based decisions.

You don't need a degree in statistics to generate evidence, but if you want to generate proof or establish causality, you should learn a bit about designing an experiment (We use the Experiment Cards).

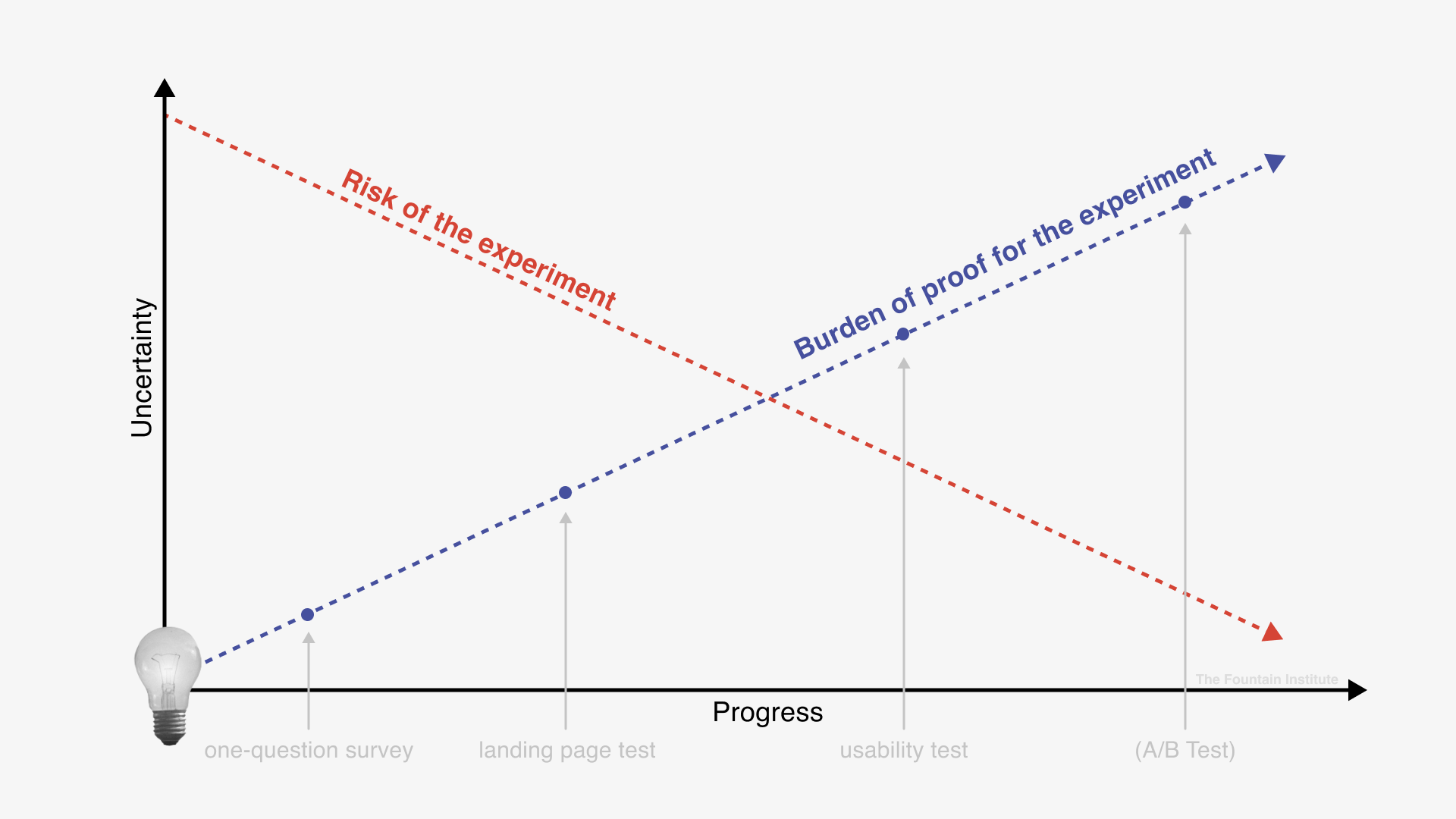

Product experiments can reveal useful correlations that you can later use to establish causality. For most teams, early signals of adoption and correlation are enough to move forward. As the fidelity of the experiment rises, so does the burden of proof

If you want to learn more about establishing proof and causality, I recommend this article on causation vs. correlation by Cassie Kozyrkov, Head of Decision Intelligence at Google. If you want to learn more about statistics in general, I recommend this free course on statistics from Segment.

Example:

Your team has a feature on the backlog that your CEO has pushed for months. Your CEO pulls you aside and asks you to send out a survey to your user testing group. You agree and look at the questions. The questions are very leading and biased towards the backlog feature. You work with her to make the questions more open-ended and provide unbiased options. You volunteer to set up a call-to-action at the end of the survey to run a desirability test. The users that finish the survey get invited to a product test where you prototype the CEO’s idea. While testing, you’re surpised to discover that user intuitively get the new feature. In fact, 4 out of 5 users ask if they can purchase the product. Thrilled by the surprising correlation between the new feature and the request to purchase, your team moves forward with an A/B Test that will provide the final proof that the idea will be adopted by customers.

Pro Tip: As you de-risk your ideas, the burden of proof will go up so make sure you work with your team to establish proper metrics for each experiment stage. Iterate through experiments until you can establish proof that your customers find value in your ideas.

Final Summary

Test assumptions. Don’t test ideas.

Every prototype should be a test.

Test Desirability, not just Usability.

Convince with data, not opinions.

Design quick and dirty, not pixel-perfect.

Design experiments bold enough to “fail.”

Generate evidence critically.

Experiments should flatten hierarchies.

Experiments are very good for the companies that run them because it creates a system for innovation that isn’t dependent on any one person. Experiments move companies away from opinions and towards evidence-based decisions. The companies that make experiments a part of their culture test every idea.

Testing ideas can radically shift thinking if your company is directed from the top. The CEO's idea? Test it. The intern's idea? Test it.

Rapid Experimentation is a series of quick, hypothesis-driven tests that let customers decide what should and shouldn’t be built through their behavior.

We don't need rockstars and experts when judging ideas based on experiment outcomes. We need critically-thinking teams. We don’t need to design stuff to appease an ego or an instinct. We need to see our ideas based on the only person who can determine our ideas' validity: the customer.

Learn More about Testing & Experimentation

Download the Experiment Cards to turn solution ideas into product experiments

Watch this talk from Cristina Colosi, innovation designer, at the Fountain Institute meetup to see how she tests innovative ideas

Learn how experimentation works with research in this article on researching vs. experimenting

Read more about Data-Driven Product Design and how it compares to data-inspired and data-informed design.

Read about how to design better A/B tests

Learn how to establish causality and proof with this article on A/B Testing by Cassie Kozyrkov

Read about testing assumptions instead of ideas by Teresa Torres

Go deep on A/B Testing with this in-depth guide by CXL

Learn how to set metrics for your experiments with the Goals-Signals-Metrics framework by Google in this article

Take the 22-day LIVE learning sprint on Designing Product Experiments by the Fountain Institute

Free Masterclass in Product Experiments

If you want to dive deeper, check out this free 60-minute webinar on how to design product experiments from the author.